|

| |

|

|

WHAT WAS CAMP-X?

The BSC’s chief, Sir William Stephenson, was a Canadian from Winnipeg, Manitoba, and a close confidant of the British Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, who had instructed him to create “the clenched fist that would provide the knockout blow” to the Axis powers. One of Stephenson’s successes was Camp-X! The book, Inside Camp-X, and the story begin, “Lieutenant-Colonel Roper-Caldbeck, the first Commanding Officer of Camp-X, stopped, stared over the rolling fields, picturesque Lake Ontario, and the newly erected buildings and thought to himself, “Everything is ready!” The Date: December 6th, 1941! That date was most significant. Had the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour been executed six months earlier, there would never have been a Camp-X. The Camp was designed for the sole purpose of linking Britain and the United States. Until the direct attack on Pearl Harbour, the United States was forbidden by an act of Congress to get involved with the war. How timely that Camp-X should open the day before the attack on Pearl Harbour by the Japanese. Even the Camp’s location was chosen with a great deal of thought: a remote site on the shores of Lake Ontario, yet only thirty miles straight across the lake from the United States. It was ideal for bouncing radio signals from Europe, South America, and, of course, between London and the BSC headquarters in New York. The choice of site also placed the Camp only five miles from DIL (Defense Industries Ltd.), currently the town of Ajax. At that time, DIL was the largest armaments manufacturing facility in North America. Other points of strategic significance in the Camp’s locale include the situation of the German Prisoner of War Camp in Bowmanville, the position of the mainline Canadian National Railway, which went through the top part of Camp-X, and that of General Motors on the eastern border of the Camp. The Oshawa Airport which was a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) / Royal Air Force (RAF) Commonwealth air training school at the time was only a short drive from Camp-X. Each of these points will be delved into in more detail throughout the book. The Commanding officers of the Camp soon realized the impact of Camp-X. Requests for more agents and different training programs were coming in daily from London and New York. Not only were they faced with training agents who were going to go behind enemy lines on specialized missions, but now they had been requested to train agents’ instructors as well. These would be recruited primarily from the United States for the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) and for the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation). Soon there were trainers training trainers for new Camps that would be set up in the U.S., primarily at RTU-11 in Maryland. To ease the demand for trained trainers, Lieutenant Colonel R. M. Brooker, a British SIS (Secret Intelligence Service) man, established a particularly successful program of weekend courses for OSS executives. (When Camp-X opened, the OSS was officially known as the Co-Ordinator of Information (COI) and did not become the OSS until June of 1942). The psychological aspect of the training was most critical. As crucial as the agent’s training in silent killing and unarmed combat was the development of his ability to quickly and accurately assess the suitability of a potential “Partisan”. He had to be able to recognize a would-be recruit by being alert at all times and in any situation. He was trained to listen for a comment about the government, about the Nazis or about how the war was progressing, and to subsequently engage the individual in conversation, perhaps offer him a drink or buy him a meal. In this manner he could further identify the individual’s philosophy and thoughts about the war. Paramount among the objectives set for the operation, including the training of Allied agents for the entire catalogue of espionage activities (sabotage, subversion, deception, intelligence, and other ‘special means’), was the necessity to establish a major communications link between North and South America and European operations of SOE. Code named ‘Hydra’, the resulting short-wave radio and telecommunications centre was the most powerful of its type. Largely “hand-made” by a few gifted Canadian radio amateurs, Hydra played a magnificent role in the tactical and strategic Allied radio networks. When one steps back and looks at the 1940 grand picture, one can see exactly why Canada was so important to the SOE as a base for their agents: if the agents were to be recruited in Canada, why not train them there? Soon the BSC had large populations of French Canadians, Yugoslavs, Italians, Hungarians, Romanians, Chinese, and Japanese at their disposal and in a concentrated geographical area. It was easier to send a few instructors over to Canada then it was to send 500 or 600 potential agents to Britain only to find that they were not Secret Agent material and afterward have to send them home. One must remember that the British were still an invasion target to the Germans. Such an invasion, if successful, would be the end of the SOE Training Schools in Britain. Thus, Camp-X became the assembly line for ‘special agents’ and subsequently the SOE. The agents trained at Camp-X would have no idea whatsoever as to their future mission behind enemy lines, nor for that matter would the instructors and/or the Camp Commandant. Camp-X’s sole purpose was to develop and train all agents in every aspect of silent killing, sabotage, Partisan work, recruitment methods for the resistance movement, demolition, map reading, weaponry, and Morse Code. It was not until the agents completed their ten-week course that the instructors and commanding officers would assess each individual for his particular expertise and subsequently advise the SOE in London of their recommendations. For example, one agent might excel in the demolition field while another might be better at wireless telegraph work. Once the agents arrived in Britain, they would be reassessed and would be assigned to a Finishing School where their expertise would be further refined. Once this task was completed, another branch of the SOE would take over and develop a mission best suited for each individual agent. Eric Curwain, Chief Recruitment Officer of the Canadian Division of the British Security Co-ordination, wrote about Canada’s significant contribution to the war effort in his unpublished manuscript, Almost Top Secret. “Previous visits to Canada could not prepare a wartime visitor for the vast war effort that at once became visible on leaving the port of Halifax to take the train for Toronto. Any Allied national from Europe must have been thrilled to see those long lines of loaded freight cars, lying in sidings, awaiting the day to pour their weaponry into the hundreds of ships that Germany’s ever-increasing hordes of submarines could never defeat.” As part of my research into Camp-X, I have been in constant contact with London, England, and specifically the FCO (Foreign and Commonwealth Office). One interesting piece of information from London I would like to share with you now. The following is an excerpt from a letter, which I recently received from Duncan Stuart, SOE adviser, FCO. “First of all, I should say that virtually no records have survived over here about STS-103. As I am sure you know, there was a bonfire of all of the New York and Canadian records at STS-103 at the end of the War. And, in any case, Bill STEPHENSON (sic) was not much in the habit of informing SOE HQ of the details of what he was up to, so there was never much information on American or Canadian matters in HQ. Moreover, SOE’s Training Section over here destroyed all its training records at the end of the War.” Thus, it will be books such as Inside Camp-X that we will have to rely upon to tell the real story of what went on behind those barbed fire fences. To meet this end, I have accumulated forty hours of taped interviews with the men and women of Camp-X as well as the neighbours of the Camp. I personally spent hundreds of hours investigating and researching in order to produce Inside Camp-X.

Often I have been asked the question, was it really worth the loss of life, and cost, to create the Special Operations Executive of World War II? My reply to this question is an immediate and unflinching; yes, I believe that it was. Many historians have also questioned the need for organisations such as the SOE (Special Operations Executive), OSS (Office of Strategic Services), BSC (British Security Coordination) and even the PWE (Political Warfare Executive) of World War II. Let’s examine just a few of what I believe were vital successes of these departments.

The SOE knew that for every 100 missions scheduled to take place, only 5% would be successful. Should this be considered a failure? Not at all; just the fact that the Allies had so many agents working simultaneously behind enemy lines meant that the Germans had to devote entire departments of high ranking, intelligent, German officers dedicating their entire war effort to tracking down every single Allied Agent which of course was an impossibility. These departments, the SD and Gestapo, were virtually tied up fighting the ‘Unconventional’ battle. Sir Colin Gubbins, Head of Special Operations Executive (SOE), wrote the following report to Winston Churchill shortly after the successful landings in France. “The stream of coded messages put out by the BBC on the evening of June 5th 1944 was directed at some 175,000 French Résistance fighters, according to plan. The response has been overwhelming. Of 1,050 rail demolition’s asked for by the Allied Command, 950 have taken place. The rail network is paralysed and German traffic, driven onto the roads, has run into countless road blocks.” This of course caused the Germans lengthy delays in getting back to Normandy from Calais and ensured the Allies a foothold on the beaches. Even with this great accomplishment, the Allies incurred terrible losses. One can only imagine the catastrophe that might have been if it were not for these brave men and women. It could have been another Dieppe. One success story, for which I haven’t written about until now, was the time when three instructors from Camp-X were sent into France just prior to ‘D’ Day and successfully blew up the most important Radar installation that the Germans had. This of course had the effect of saving hundreds if not thousands of Allied lives. That’s just one of the 500 stories; most of these stories have gone to the grave along with the brave men and women who owned the right to stand up and proudly say: I did make a difference.

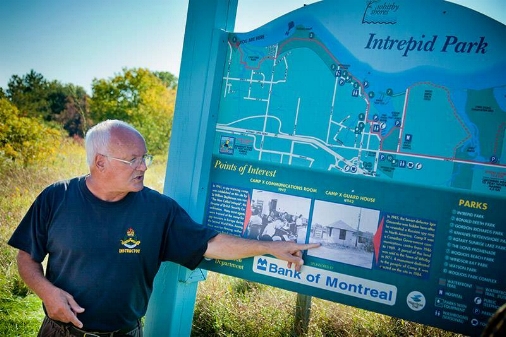

During my research of the ‘top secret’ spy school, ‘Camp-X’, I had the pleasure to meet a man named Andrew (Andy) Durovecz, non-de guerre, Andy Daniels. Andy was much different from other secret agents as he was in his thirties when he left Camp-X for his secret mission behind enemy lines. I mention this because by the age of thirty, most of us have matured to the point that we recognise danger and fear whereas a person in their early twenties, knows no fear. This of course is why young people of the age of 19 or 20 are selected for dangerous missions. Imagine being told at such a young age that you have a 50/50 chance of surviving your mission and this would depend on how well you listened and learned from your instructors! On a cold November day in 1977, I was able to convince Andy to return with me to those windswept fields of Camp-X. There, reminiscences of life at Camp-X came back to Andy like being hit by a bolt of lightning...

He took another sip from his flask of rum while he stared at the light, which constantly flashed in his face, wondering how soon would it turn green? At that moment he had no idea where he was, only that soon he would drop through that chute and into the unknown. What would be waiting for him when he reached the ground? Had the enemy been tipped off about his arrival? Would the Gestapo be waiting for him when he landed? He took another sip from his flask and stared at the flashing light... Andy thought back to the day when he had sat in the shade of a tree trying to escape a June heat wave at Camp Borden, Ontario. A corporal came running in his direction. “Private, the Commanding Officer would like to see you,” the corporal said. Andy went to the CO who ordered him to report to the Canadian National Exhibition Grounds in Toronto, a staging area for soldiers about to be shipped overseas. Once there, eight other Hungarian/Canadian boys, all of whom he recognized, joined Andy. They were all packed into an army Jeep, and then later into a civilian car, and in less than two hours, they arrived at Camp-X. Of course, Andy had no idea where or what this place was. All he knew was that they were in a secluded, secret Camp. As Andy and the others stepped into the building to which they had been directed, he immediately knew where their mission would take them. The reception room had been converted into their Hungarian “homeland” complete with food, folk art pieces, and wine. Training started that first night—drinking good Hungarian wine! Naturally, the young recruits did not look upon this as a training exercise but more as a reception or a bit of R & R before their actual training would begin. Their trainers, however, certainly took it more seriously. This was the very purpose of the exercise: to learn to be able to drink as much as was possible and still hold your tongue. Some months later this training paid off, as will become apparent as Andy’s story continues to unfold. Training went on day and night. Daytime instruction dealt with the basic skills; then, as the trainees advanced, nighttime instructions were added. The training was intensive, to say the least. Every minute of the day was filled. The agents were kept either running or crawling; they seldom walked anywhere. They might be either silently crawling up to a target or stealing away from it. The same exercise was repeated over and over until it was pounded into them and became an integral part of their nervous systems, until each reaction was so automatic that it became a sixth sense. “We had to go into a dark room in the old Sinclair farmhouse where we would find a bag of gun parts. Still in the dark, we had to put them together and come out shooting.” An obstacle course was constructed through which the agents suffered the most rigorous and gruelling instruction. Specialty equipment was often received from American manufacturers, occasionally obtained with the direct intervention of President Roosevelt. Corning Glass received a request for, and subsequently provided, a sheet of bullet-proof glass some six feet high and nine feet wide. Agents would stand behind this glass while live ammunition was fired directly at them from short range. The following pictures were smuggled out of Camp-X, copied, and actually appeared in a local Toronto newspaper in 1943. They were then smuggled back into the Camp. The agent-in-training responsible for this ‘operation’ had created a cover story to protect himself. If he were to be caught, he would simply say that he was practicing what he had been taught to see how proficient he was, and then he could return the pictures immediately. As it turned out, he did not get caught and he performed his self-proclaimed mission successfully. Photographs such as this of the agents’ training were taken routinely and became part of Major Fairbairn’s Instruction Manual. One might wonder why it was so important to the agent in the field as well as the guard responsible for guarding the Camp to both be trained in all of these procedures. Whether the agent was attempting to “infiltrate” the Camp, or the guard was trying to prevent him from doing so, it was beneficial to both to understand the actions of the other. One only need read the following quote from Andy (Durovecz) Daniels’ book, “My Secret Mission”, to see why. ”I was questioned by the Gestapo as well. Once again I had to describe the methods and locations of my training, but I told them no more than I had told the Hungarians. Since I had come through Slovakia, they too tried to discover, by fair means or foul, whether I was not a “Bolshie” and a Soviet agent, giving me many a beating in the process. What they really wanted to know were the intentions of the British concerning Hungary. Where, and in which direction would the British carry out a major attack on the Balkans? How many British soldiers and airmen were being prepared for action in Hungary? I could honestly say I didn’t know. “Once, while questioning me, the Gestapo suddenly started talking about Camp-X! Where was it? What kind of training took place there? They asked me much that I really did not know. We did not even know at that time about the code name, “Camp-X”; the people around Whitby and Oshawa had merely called it “the secret military camp”. This showed how well informed the Abwehr (the German Military Intelligence) were; they even knew the code name. But they did not bother me much about this, perhaps because they knew no more, perhaps because my demeanour suggested it really was news to me.” My old friend Andy was right. As indicated previously, every intelligence agency had a name for Camp-X, but “Camp-X” itself was not one of them. The name “Camp-X” was given by the locals at the time of its construction when they first became aware of the mysterious goings on behind the fences. Could it be that the German intelligence agents got so close to Camp-X that they believed the actual name of the Camp to be “Camp-X” because the locals living in the surrounding area referred to it as such? It is not unrealistic that the Germans were aware of Camp-X. We now know that German records captured by the Allies at the end of the War clearly indicate that the Germans were aware of every aspect of the English Camp, Beaulieu, right down to the name of Lord Montagu’s dog. The Montagu family owned the Beaulieu Estate. Merv Allin recalled working in his brother’s field, which was on the east side of Thornton Road. He hid in the dense grass by the side of the road and watched the agents down by the lake placing trip wires across the road. As a car would come down the road, it would set the charge off as it passed by. Not enough of a charge was placed to do any damage, but enough to illustrate what could happen if this were done in a real scenario and how easy it would be to blow up the car and its occupants. At the end of a rigorous day of training, the agent would return, totally exhausted, to his room for some relaxation. Upon entering, he might notice that something was missing or misplaced. This taught him the extreme importance of observation. A mental note of the situation was recorded for future reference should it ever become an issue in a future training lecture. In the morning, very tough instructors, the majority of whom were from England, led exercises. Andy remembered one in particular, a very proud Scot who always wore his kilt. Another, who had already served in Europe, had a limp but was a bright, wise, and clever instructor. The Scot instructor once said, “I’m going to go to Churchill and tell him to give us one hundred Hungarians and one hundred Scots and together we are going to ---- Hitler.” (Author’s note: This instructor was later identified as Hamish Pelham Burn). He was truly fond of the Hungarian lads. Andy thought that they and the instructors shared a peasant background, which made them able to relate to each other. There was also some mysterious “seventh sense” which bound them. The Hungarians were believed to be ideally suited for the Secret Service because they demonstrated a relentless determination, great stamina and held strong political beliefs. After the war, Colonel F. H. Walter, O.B.E. (Order of the British Empire), said; “It was only at a later stage that it was realized by Special Forces and by the British military authorities generally that the national resistance movements in themselves were powerful potential military forces. From that time forward the SF agent ceased to be merely a saboteur and became, in addition, a liaison officer and an expert in weapon training, in supply, in tactics and in leadership.” Andy and his mates were recruited and trained for guerrilla warfare. At the Camp, the emphasis for them was on tough physical training. A typical manoeuvre might entail running full out and jumping off the towering cliffs to the lake below, then climbing back up from the shore to the highest point of the cliff by rope. Only nine of the original twenty-two completed the rigorous training and went on to the next phase. The intelligence training, initiated at Camp-X and continued in England, prepared them not as spies but as agents. (Author’s Note: During my investigation of Camp-X, I had been told that one of the reasons the Whitby/Oshawa shoreline of Lake Ontario had been chosen was due to the uncanny similarity of the beach front to the shores of France, gradually sloping eastward toward the thirty foot high cliffs. In a later interview with Tommy Drew-Brook, head of the Canadian Division of the BSC, I learned that this, in fact, had nothing to do with the decision to pick this particular site. The coincidence of the similarity did make it extremely convenient, however.) Live ammunition was used in all practices. No one shot directly at the agents-in-training of course, but the stress of knowing that live ammunition was being fired your way added to the sense of realism and reinforced the seriousness of the exercise. It was survival training in its truest sense. It taught the agent to keep his head, but at the same time made him angry and determined. The agent-in-training also concentrated on demolition; factories, railways, bridges, and locomotives were frequent and logical targets. On one such exercise, Andy and his fellow agents were in the Toronto railway yards (Union Station) where they decided to ‘steal’ a locomotive. One of the men asked the others whether anyone knew how to operate it and the answer was unanimously, “no.” After careful consideration, and in spite of this minor detail, the decision was made to proceed anyway. They managed to get the train moving down the line, but could not figure out how to switch it. Soon they realized that there was a train approaching them on what appeared to be the same line. They quickly jumped from the train and ran as far and as fast as they could to avoid the explosion from the expected inevitable collision. But the train carried on, slowing down, until it gently bumped another train and came to an uneventful stop. The agents, upon returning to the Camp, informed their instructor what had transpired. The proper authorities were immediately dispatched to Union Station to explain to the manager just what had happened and to instruct him to consider the damage as the Station’s part of the war effort. He received no further explanation. As long as these exercises were properly executed and no one was injured, there was never any objection from the Camp instructors. There was always someone available from the Camp to serve as “damage control” after the agents had left the scene, and the agents knew that the Camp authorities would always cover their tracks. Of necessity, the Camp had devised quite a unique plan of action in the event that one of their agents got into trouble. It was essential that the Camp be able to locate and retrieve the agent, as well as to satisfactorily explain his actions. On one particular training mission, one of the trainees was apprehended and the police were called in. When the agent was confronted with handcuffs, he requested that the RCMP be contacted with a message: “S25-1-1” (the secret RCMP file number for Camp-X). Inquisitively but reluctantly, the policeman phoned and relayed the message. Within fifteen minutes, an RCMP officer was on the scene and told the policeman that he would take care of the incident and that if the police had any further questions they should contact Inspector McClellan at RCMP H.Q. Within the hour, the agent found himself back at Camp-X. The agents “hit” many local targets, including General Motors in Oshawa, the port of Toronto, and especially the Toronto/Montreal rail line. Andy could not recall the number of times they simulated blow ups of trains using fake plastique (RDX) explosive developed by the BSC at Ajax (DIL) and Camp-X. Agents learned that derailment caused the enemy some headaches, but could be repaired in a few hours and really proved to be little more than a nuisance. A truly effective delay could be caused by taking out a site such as a bridge or a viaduct, which could potentially take days to reconstruct, and required a greater number of personnel to complete, a recurring objective in the training program. Kother able-bodied men were kept from entering combat, as their services would be required in various support tasks to assist in tending to the wounded personnel. Instead of taking out only one of the enemy, several could be removed from combat at the same time. To be able to shoot a target with a revolver or a pistol from a distance of twenty feet required much practice and training, most of which was carried out in the underground firing range. There was not a ray of light, not even the light of the moon. Shooting had to be by instinct, by sensing movements, even perhaps utilizing the sense of smell. There was no option - the agent must hit the target, he HAD to. He was trained, grilled, almost tortured mentally until he hit that target. That was all there was. It was just part of the training. “The night manoeuvres were bloody awful,” recounted Andy Daniels. The agents would be taken by Jeep to the area around Port Perry, Orono, or perhaps to Rice Lake, near Peterborough. They would be given a map and compass, told their target and left to find their way back, completing the mission. “Meanwhile, the instructors would sit playing cards, or sipping a beer, waiting.” When the agents arrived on target, hours later, they would be loaded into a Jeep, tired and hungry, and would head for Camp. As often as not, though, they would not reach Camp, but would be told that there was a new ‘situation’, be given their new targets and they would stagger off in all directions to fulfill yet another mission. On night manoeuvres, they would sometimes land a little Tiger Moth in the open field on the far side of Corbett Creek near Camp-X. The trainees would then have to scramble through the brush and be on board in less than a minute. This particular training manoeuvres began for Andy when he was selected to practice entering enemy territory as a secret agent. The rest of the group was to be resistance members. Andy was taken to Oshawa airport and put in a Tiger Moth, which landed a few feet outside the Camp fence directly across Corbett Creek from the buildings. The receiving party, other agents in the role of resistance fighters, was waiting for him, and together they would ‘infiltrate’ the Camp. The Camp guards were awaiting them but the ‘Partisans’ eluded them by crawling to their target, one of the Camp buildings, and laying a charge. Andy and the others retreated having succeeded in their mission. The timing of each guard watch was never routine but always random. The guard never made a perimeter check at the same time after the hour, as did the previous watch. This, of course, was by design in order that any observer would not be able to predict when a guard would pass by any given check point on his watch, thus making it more difficult for any would-be infiltrator. The Hungarian agents’ training took about twelve weeks to complete that summer of 1943. They had landed at Camp-X sometime in the middle of June, and they departed in the last days of August. All in all, it was very rigorous, extensive training and they emerged from Camp-X hardened beyond any other military, physical, mental, or emotional experience that they would endure in life. Directly from Camp-X, the agents were shipped overseas on the “Queen Elizabeth.” When they arrived in Glasgow, there were twenty two thousand troops on board the ship. Andy remembers that they had to sleep in three shifts and, if you did not get any sleep on your shift, you were out of luck. They were all dressed in Canadian uniforms, complete with Canadian insignia. No one had any idea that they were secret agents, as they looked exactly the same as any of the other thousands of soldiers on board. Training continued at another SOE school in Scotland. Andy was then shipped out to Cairo where he had his first chance to test his skills learned in the weeks of preparation at Camp-X. He wandered into a bar and sat down at a table alone. Shortly after ordering, he was joined by a friendly chap who wanted to talk and buy him drinks. A few well-placed questions on Andy’s part soon convinced him that the man was not quite what he presented. Andy determined that he was an Abwehr Agent (German Military Intelligence) and was also certain that he knew Andy’s identity as well. The drinking began in earnest. Anyone watching them would have thought they were a couple of drunken soldiers, what with the quantity of booze they were each putting away. Damned if Andy did not outlast him, though. He literally drank his companion under the table. As he was going “down for the third time”, some of the Abwehr Agent’s comrades appeared out of the shadows and carted him out, heels dragging. Never before, nor since, had Andy drunk so much. His hangover lasted a week! From there the agents went to Bari, Italy, to prepare for their missions and take a well deserved rest, exactly what they would need when one considers what was in store for them. Regarding Bari, Italy, Eric Curwain, the Chief Recruitment Officer for Camp-X, would later write, “Our special Signals Unit in Bari was administered from a building next to a church and had everything a field office of that type should have; photography unit for faking documents, engraving and printing equipment, coding and decoding staff. Attached was a radio interception and transmitting station to maintain contact with agents in Yugoslavia, northern Italy, Austria, and Hungary and with our Ops. Room at headquarters in England. “There was also a school for training agents in Morse and in the use of mobile field transmitters. One of the instructors was an Italian who had returned from a mission with his fingernails mutilated by his German captors when he had landed from his canoe at the wrong spot on the Adriatic coast near Ancona. “There was a store of foreign-type clothing for agents dropping into countries of which they were usually native or linguistically suited to pass as such. It contained a strange collection of gadgets and stores for the use of parachute types (sic), ranging from currency to whiskey, cigarettes, to fly buttons containing tiny compasses and beautiful maps printed in silk. When the Germans discovered that men’s fly buttons hid compasses which screwed into one half of the button, the British inventors reversed the thread and this fooled the Germans into believing the buttons were normal, since they could not unscrew them by turning them in the usual direction.” Andy came out of his thoughtful stupor and resumed looking at the flashing red light. The dispatcher stood by the door having already performed half of his duties in preparing Andy and the others by hooking up their static lines. Andy was just as glad that the dispatcher had hooked him up because he was too nervous to do it himself. They were flying over Hungary, at well above twenty three thousand feet. Andy could hear the anti-aircraft artillery booming all around the Halifax and he prayed that one would not hit the plane. They were, in fact, too high to be in range, but Andy and the others could not know that at the time. Andy could see the ack-ack bursting all around the drop chute. He recalled that it looked like Christmas lights to him. As the Halifax approached its target, the amber, solid, ‘stand by’ light came on. This is it, Andy thought. There was no stopping now. All of his training would lead to this one jump. The time was near. Soon the light would turn green. “Right lads, come on now, and let’s get ready,” barked out the dispatcher. Andy thought, “You have to be either drunk or crazy to jump out of an aircraft at this altitude, perhaps into the arms of the enemy.” Each of the men had a number, which designated the jump sequence. Andy was number two. Number one was Major ‘S’, an Irish Catholic. He had never touched alcohol. Never. Andy and the others were each allowed a flask of rum to carry in their jump suits. It would help to keep them warm and would make the trip down a little easier, Andy thought. Major ‘S’ had turned his down. Finally, the ‘green’ light came on; it was time. Andy pulled out his flask of rum and went to take another swallow. Just as he put the flask to his mouth, Major ‘S’ said, “Give me that!” grabbed the flask from Andy and downed the rest of the contents in a mighty gulp! “Time!” yelled out the dispatcher. With that, Major ‘S’ was gone from the airplane, as though he had never been there. “Right then, number two, you’re out!” In the fraction of a second before Andy jumped, number three gave him a swallow from his flask. It was greatly appreciated. Half way down, Andy realized that he was stone cold sober and, by the time he reached the ground, he was as cold as death. But the biggest surprise was still to come. “Someone had miscalculated!” Just on the other side of the hill, about a mile away, were the Germans. Andy thought to himself, “this is not a good beginning for my first mission” as he struggled to cut his shroud lines. He had gone from the relative safety of the Halifax twenty three thousand feet in the air, to sitting in the middle of a hornet’s nest on the ground. As he struggled to get out of his overalls, he could hear the slightly off-sync drone of the Halifax’s engines; minutes later he was free of the lines and his parachute. Several more minutes passed before he found his jump-mates, one of who, an expert map-reader, informed them that they were lost! Although later evidence was to prove him correct, this intelligence was not at all well received at that particular moment. Readers who have examined the appendices in SOE In France will perhaps be familiar with the instructions which were given to pilots engaged in dropping agents, to the effect that navigation by visual ground references at night can be terribly misleading. The author of these Notes For Pilots, Wing Commander H. S. Verity, DSO, DFC, reports that he became confused as to which of two villages he had approached, and spent ‘two miserable hours’ trying to sort things out. The error later proved to be even greater than he had anticipated by some eighteen kilometers! However, with the enemy only metres away, there was nothing for the agents to do but to find shelter and get some rest before attempting to straighten themselves out. Accordingly, they spent a miserable night huddled together in the woods. At daybreak they decided that it would be best to split up. They did so, with the understanding that they would meet up some time later at a safe house in Budapest. As he traveled from village to village, Andy became increasingly aware that the Germans were closing in. There were soldiers everywhere. His brain automatically clicked into training mode and he ducked into an abandoned building, changed into his priest’s vestments, and continued safely on his way, blending inconspicuously into the local populace. Andy determined that his best course was to seek out a ‘halfway’ safe house, in a small village along the route, but in his haste to find sanctuary, he very nearly blew his months of training. Upon arriving at the correct address, he mounted the front steps in his best ‘homme du monde’ manner, and rang the doorbell. In a moment, a lady greeted him and he inquired for her husband. She stepped back, visibly shaken. After what seemed like an eternity, she said that her husband had been dead for six months. For a moment, Andy was unable to explain her behaviour to him. Then, it suddenly occurred to him that he had not given her any of the pre-arranged passwords. He was mortified. He had failed his very first test. In his confusion, he muttered the words and, just as he turned to leave, she motioned to him to enter. Gratefully, he followed her into the house and she closed the door behind him. For months, she said, she had been rehearsing the code words, in the expectation of Andy’s arrival. His direct inquiry for her deceased husband threw her into a panic. Was Andy the Gestapo? In one agonizing moment she had, ‘evaluated your veracity, and decided to trust you’, she said. Andy remained there for several days. They became quite fond of one another, but he eventually left to meet his comrades. On his return to Hungary in 1979, as he tried to retrace each step of his mission, he found himself on those same steps, thirty-six years later. His anticipation of a joyous reunion knew no bounds. But a stranger opened the door. “No,” she said, “Mrs. … doesn’t live here anymore.” The response to his request for her new address hit him like a hammer blow: “Mrs. … was taken by the Gestapo, in 1944. We think she died in Belsen. They said that she had been found guilty of harbouring a British secret agent.” After the war, Andy wrote to England inquiring about information on him for his now published book, “My Secret Mission”. The reply; “You joined STS 103, in mid 1943…. You arrived in England on 18 September 1943. Here you continued your training as a W/T operator and sabotage agent in various SOE Training Schools. You proceeded to Cairo in February 1944. In May you were transferred to Italy. From Bari you were parachuted on 18 September, 1944, in the name of Lieutenant Andrew Daniels, into Slovakia, with three other officers, to establish contact with the Slovak Headquarters at Banska Bystrica which was organizing the Slovak rising. “There you were instructed to cross into Hungary in civilian clothes to make a reconnaissance and obtain papers and safe addresses to which the other three officers could eventually proceed. You crossed the frontier on 19 October and reached Budapest safely. But as it proved impossible to obtain the necessary papers, you decided to return to Slovakia to rejoin the three officers at Banska Bystrica. However, when attempting to re-cross the frontier, you were arrested and imprisoned by the Hungarians. By the end of October 1944, the Slovak rising had been suppressed by the Germans and the three other officers had escaped into the hills, where they were subsequently also arrested. “You remained in Hungarian prisons at Misols and in Habik where you met the SOE-trained Mike Turk and “G”. You succeeded in escaping and remained in hiding in Budapest until the Russians occupied it. They evacuated you, thus enabling you to proceed, via Italy, to England. You arrived in London on 23 May, 1945, and returned to Canada on 7 June, 1945.” After some time, Andy was transferred from the prison to a temporary internment camp. Andy and the others were on their way to one of the death camps inside the Reich. Andy escaped during his fourth night at the new camp. It was a dreary, rainy night. Andy and his fellow captives were allowed to get some wood for a fire, but it was wet. They plugged up the pipes of their heater, lit the fire with the wet wood which began to smoke heavily, and as the guards ran into the room, they slipped out the side door and made their way back to safety. After the war, Andy returned to Hungary for the purpose of doing research for his book. He tried to re-enter the place where he had been imprisoned by the Hungarian Counter Espionage and the Gestapo at the time when the Red Army was getting near. They would not let him enter, as it was still a military barracks at that time. He had hoped to be able to find some record of his stay there, but to no avail. The Gestapo had destroyed all records when the Red Army was approaching. For two days and nights, they had burned the records in the courtyard where previously the executions had taken place. Andy returned to Camp-X one cold November day in 1977. I was his guide this time as I was more informed regarding the current condition of the Camp than was Andy. All that was left of the Camp were the concrete foundations. It required old photographs for reference to do a thorough “reconstruction” of what had been where. “So this is Camp-X,” said Andy, as he looked around the barren fields, his eyes piercing through the overgrown grass in search of ghosts in the shadows. “There,” he said, pointing toward the southeast and Lake Ontario. “That’s where a good part of our training took place; the explosives. I remember the Sunday afternoons we had off. We would play football (soccer) for hours. The Camp trainers loved it because the physical training was great for us. Those damned craters!” said Andy. “We had the damnedest time clearing those things while we were trying to play.” The explosions of the previous day’s training of course caused the craters. As he told me, the one thing that he remembered most out of all of his training, was the open field ‘evasive’ exercise. “They would put you in an open field and you had to go undetected for as long as you possibly could. The way to do this and be undetected was to remain perfectly still as it is difficult to see an unmoving target. If you moved and were spotted, a round of fire over your head would signify that you had been spotted.” The other thing that Andy always remembered was how he was taught to ‘take a man out’. They would teach the agent, “Do not go for the testicles from the front, go for them by way of the back which puts you in better control.” And finally, “Stick your fingers into their, ears, eyes or nose with full force as the individual must give this his full attention giving you time to ‘finish him off’.” Andy gazed in the other direction, north toward the trees that still lined the original roads. He thought back to the cold, dark prison where he had been interned after he had been captured. He thought about the torture and the constant interrogations. After all, that was where he had lost his innocence. Life had been so much simpler here at the Camp. Even in the most rigorous times in the training program, if you made a mistake, someone was quick to point it out to you and everything could be taken back or done over. Upon Andy’s return to Toronto, he settled down and got married. Unfortunately, all his years of training and his experiences as a secret agent would eventually take the inevitable toll on Andy as on so many others, not just the agents, but also anyone who had lived through or served in the war. It seemed perhaps to affect the agents more than others because of the type of training that they had been through. As was understandable, Andy did not want to talk with his new bride about his experiences during the war. As a result, when his behaviour began to change later on, she had no idea how to cope. Andy began to have terrible nightmares of being captured by the Gestapo and about the subsequent torture he had endured. To someone who has never experienced such treatment, you can only try to imagine yourself laying flat on a board, nude, and having live electrical wires attached to your testicles. Should you not answer the interrogators’ questions to their liking, they would flip the switch. Try to imagine also knowing that you would continue to receive increasingly stronger jolts as long as you persisted in giving unsatisfactory answers until either you gave in or passed out. To Andy, this had been reality. Andy’s nightmares became more frequent as time went on, but still he could not disclose the torment he suffered. He would jump out of bed in a cold sweat in the middle of the night. His wife tried to understand, but never knew what caused his violent behaviour. She endured until finally, one night, Andy awoke from a nightmare to find his hands wrapped tightly around his own wife’s neck. This was the end of Andy’s marriage. He never remarried. Andy died alone in 1998. |

(289) 828-5529 (289) 828-5529 |

||||

|

Students & Teachers |

Store |

History of Camp-X |

Of Interest

|

All content, logos and pictures are the property of Lynn Philip Hodgson and cannot be published without written consent.

Copyright © 1999